Natalya Romaniw’s performance in Garsington Opera’s first production of Rusalka was delayed by Covid for two years. Then mid-run the Swansea-born soprano tested positive and Elin Pritchard jumped in and by all accounts gave the audience a much-enjoyed performance. By the start of July, Covid-free, the singer returned to the stage, and it was this first performance of her return to the role that I attended, Garsington’s cast now complete as other principals had also temporarily withdrawn from shows. The resulting evening was as magical as the Slavic fairy-tale on which it is based, with a performance from Romaniw as spellbinding as it was unforgettable. The wait has been well worthwhile.

Now also scheduled for the Edinburgh International Festival in August, young Welsh director Jack Furness has given us a nature-meets-industrial age feel for the tragic tale. It suggests the effects of mankind destroying the natural world, as well as the fatal consequences of the water-nymph Rusalka’s desire to experience human love. It is her longing to be able to win the love of a Prince who visits her idyllic forest pool that is the subject of the opera’s best-known aria, Měsíčku na nebi hlubokém (Song to the Moon). Furness does not dive into pschological interpretations as some directors have done to varying degrees of success, and the emotional and physical / sexual aspects of the story are not laboured.

Natalya Romaniw and Gerard Schneider

Natalya Romaniw and Musa Ngqungwana

Despite being warned of the consequences of leaving her family and her own world behind, Rusalka turns to the witch Ježibaba for the potion that will give her human form. Ježibaba warns Rusalka of the dangers of mixing with fickle men which can only result in heartache and worse. Should he prove false, not only will he die but she will be eternally damned to the watery depths. Of course, she also must give up her voice to join the race of humans.

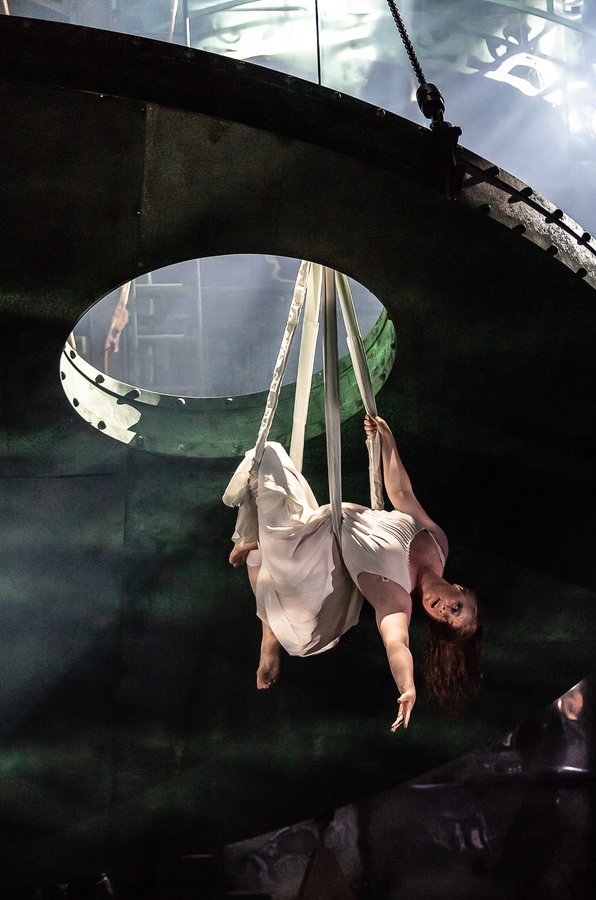

Designer Tom Piper has created an elegant late Victorian cast-iron pavilion, with ladders and walkways, with a rising and falling metalwork aperture. This appeared like a lid, almost like a huge metal manhole cover placed by the toxic humans on the natural world of Rusalka and her water world family and other creatures, gorgeously lit by Malcolm Rippeth.

The iron gantries allow for Furness to employ aerial rope dancers to be all manner of gyrating sprites interacting with the three nymphs sung by Marlena Devoe, Heather Lowe and Stephanie Wake-Edwards who, Rhine maiden-like, are the first to be heard in the opera, and reappear as the story unfolds. Choreographer Fleur Darkin and circus choreographer Lina Johansson create an enchanting lively, free-spirited spectacle that contrasts with the staid, formal inhabitants of the Prince’s palace.

Natalya Romaniw

Bringing the clash of the nature with the human world darkly to the fore, the ropes are used in the second act, in the human world, to hang dead deer that will be eaten at the Prince’s wedding feast. Not surprisingly Rusalka is disgusted by this sight. It was during a hunting party the Prince first came across Rusalka in human form (mistaking her for a white doe), and it is a gruesome but fitting metaphor when he butchers a deer on stage ripping out its heart. Much is also made of the contrast between Rusalka’s aesthetic love, and the sexual passion offered by her rival, the Foreign Princess, with the wedding bed becoming a place of horror for the innocent half-human bride.

The production delights in the superstitious / supernatural elements of the story, with the witch Ježibaba’s hut being a large human skull. The witch, sung by Christine Rice and dressed as a Slavic grand dame, toys with the gamekeeper and cook’s apprentice, sung by John Findon and Grace Durham, who come to ask for her intervention and are comically spooked by having to visit her. Their scene in the kitchen, turning the spit with one of those deer, is another rare ray of humour in the dark tale.

Christine Rice

The evening was filled with intoxicating singing and not only from a sensational Romaniw, who brought her natural Slavic singing to add to the power and elegance of her warm soprano. The role acted as a showpiece for her vocal dramatic range and comfortable stage presence, including some nifty ropework. What a delight Royal Opera audiences have in store when she makes her full opera debut in the role of Tosca. Gerard Schneider was a deeply sympathetic Prince, a romantic, troubled soul, bright toned singing with elegance and weight. The final duet when in Act III Ruslaka is a ‘bludička’, a spirit of death whose kiss literally kills the man she loves, was achingly beautiful.

Musa Ngqungwana sang a glorious Vodník, Rusalka’s water goblin father, bringing a caring paternal touching pathos to the role. As the witch Ježibaba, Christine Rice, conjured her potions and spells with relish. At the rapturous curtain call for the magnificent cast, Sky Ingram acknowledged the near panto villain role of the Foreign Princess, having played the role with a cold, calculating presence.

The Philharmonia Orchestra, under the baton of Douglas Boyd, gave a lithe reading of Dvořák’s mesmerising and seductive score that shimmers like the watery lights of the forest lake.

Until July 19

Images: Clive Barda.